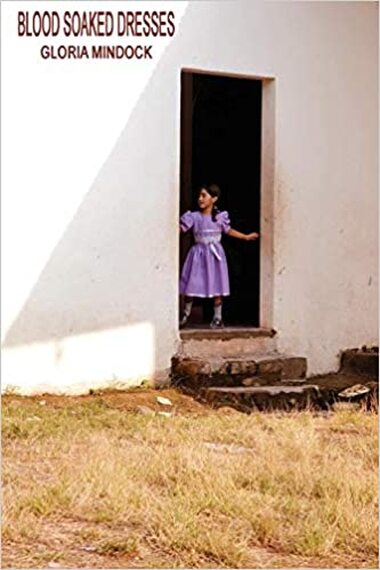

Blood Soaked Dresses

(Ibbetson, 2007)

GLORIA MINDOCK

In her fascinating poem cycle, Gloria Mindock jolts back into memory the roots of El Salvador's present day violence. Mindock coaxes to the page the voices of the dead who lie, less in peace, than in restless obsession with the atrocities they suffered. She brings forth as well the voices of the living who seem startled to find that they died somewhere between the horrors they witnessed and the grave they have yet to lie down in. Blood Soaked Dresses is a beautiful, harrowing first book.

-Catherine Sasanov

(Ibbetson, 2007)

GLORIA MINDOCK

In her fascinating poem cycle, Gloria Mindock jolts back into memory the roots of El Salvador's present day violence. Mindock coaxes to the page the voices of the dead who lie, less in peace, than in restless obsession with the atrocities they suffered. She brings forth as well the voices of the living who seem startled to find that they died somewhere between the horrors they witnessed and the grave they have yet to lie down in. Blood Soaked Dresses is a beautiful, harrowing first book.

-Catherine Sasanov

More Praise for Blood Soaked Dresses

A poet must never shy from the necessary, no matter how hard it is. In poetry that is both elegant and brutal, Gloria Mindock exposes the horror of the Salvadorian conflict especially on women. Though Salvador has faded from the front pages, the war has reincarnated in other countries on other continents making “Blood Soaked Dresses” completely contemporaneous. This poetry possesses, as Yeats said, “a terrible beauty.” And we need it now more than ever.

-John Minczeski

-John Minczeski

The reader of Blood Soaked Dresses is enriched by Mindock's power and commitment. She has earned a place among our great protest poets, and reminding us, with lyric tension, that social justice is our constant necessary concern.

-Simon Perchik

-Simon Perchik

We are reminded of Cezar Vallejo’s witnesses: bones, solitude, rain, and the roads – that we are tied to each other in beauty and suffering, life and death. Gloria Mindock’s poems grant us the voice of a soul caught on a limb between the promise of peace everlasting and impossible resurrections. Poem after poem we are asked to uncover those whose bitter ash weeps over the world, and no other country/wants to see it. This book is written from a compassionate heart that whispers and grieves, one that isn’t afraid to hold its gaze.

-Dzvinia Orlowsky

-Dzvinia Orlowsky

The Boston Globe

Poetry on El Salvador forces readers to see human tragedy

By Ellen Steinbaum

Globe Correspondent / December 9, 2007

This month of holiday lights and frenetic cheer opened with World AIDS Day, reminding us of a disaster we are in danger of forgetting. It is one I have felt compelled to write about often through the past two decades. That is what writers do: We refuse to not see.

Every day we wake to newspapers full of new human catastrophes of all types in various places, year after year, decade after decade. Bosnia, Aceh, Sudan, Bhopal blur in our minds into a vague disaster stew. And though we are caring people, we are human and the tragedies are painful. So we ignore. We forget. Unless someone insists on reminding us, as Gloria Mindock does of the civil war that raged in El Salvador from 1980 to 1992. In her new poetry collection, "Blood Soaked Dresses," she holds up the events so we cannot look away.

Mindock, recipient of a Massachusetts Cultural Council grant for poetry, is the author also of two chapbooks and the forthcoming collection "Nothing Divine Here." She is the editor of the Cervena Barva Press and the online journal Istanbul Literature Review, and is a former editor of the Boston Literary Review.

The poems from "Blood Soaked Dresses" began when Mindock had the opportunity to speak with refugees from El Salvador.

"I'm very political," she says. "I get so angry when I see what mankind does to mankind."

She says the book is written in memory of one of the refugees she interviewed, Rufina Amaya, who was the lone survivor of an infamous massacre in which the entire village of El Mozote, including Amaya's family, perished at the hands of the government-linked Alianza Republicana Nacionalista, or ARENA, death squads.

"They would hang body parts in the trees. One woman saw her husband's hand with his wedding band on it, and that's how she knew he was dead," Mindock says, adding that the stories were so horrifying to her that writing about it felt almost like a calling.

Now she wants us to remember that as long as there are survivors to remember, tragedies continue to echo long after the news photographs and on-the-scene reports have faded. And even without survivors, the facts remain. And so Mindock has made it her mission to bear witness, as centuries of writers, composers, and visual artists have done before.

"Blood Soaked Dresses" begins in Rufina Amaya's voice: "Death crawls underneath this world and waits. Who will be next? Three months ago, the soldiers murdered my two little girls. . . . Their screams were like bad music. . . . I talk to them every morning. . . . At night, they invent my dreams."

Mindock continues her book with the sad indictment that, no matter how high the cost in human suffering, our attention will not be held. We will forget, turn away, move on with our lives. But maybe we can be persuaded to remember, if only for the time it takes to look at a painting. Or read a poem.

Poetry on El Salvador forces readers to see human tragedy

By Ellen Steinbaum

Globe Correspondent / December 9, 2007

This month of holiday lights and frenetic cheer opened with World AIDS Day, reminding us of a disaster we are in danger of forgetting. It is one I have felt compelled to write about often through the past two decades. That is what writers do: We refuse to not see.

Every day we wake to newspapers full of new human catastrophes of all types in various places, year after year, decade after decade. Bosnia, Aceh, Sudan, Bhopal blur in our minds into a vague disaster stew. And though we are caring people, we are human and the tragedies are painful. So we ignore. We forget. Unless someone insists on reminding us, as Gloria Mindock does of the civil war that raged in El Salvador from 1980 to 1992. In her new poetry collection, "Blood Soaked Dresses," she holds up the events so we cannot look away.

Mindock, recipient of a Massachusetts Cultural Council grant for poetry, is the author also of two chapbooks and the forthcoming collection "Nothing Divine Here." She is the editor of the Cervena Barva Press and the online journal Istanbul Literature Review, and is a former editor of the Boston Literary Review.

The poems from "Blood Soaked Dresses" began when Mindock had the opportunity to speak with refugees from El Salvador.

"I'm very political," she says. "I get so angry when I see what mankind does to mankind."

She says the book is written in memory of one of the refugees she interviewed, Rufina Amaya, who was the lone survivor of an infamous massacre in which the entire village of El Mozote, including Amaya's family, perished at the hands of the government-linked Alianza Republicana Nacionalista, or ARENA, death squads.

"They would hang body parts in the trees. One woman saw her husband's hand with his wedding band on it, and that's how she knew he was dead," Mindock says, adding that the stories were so horrifying to her that writing about it felt almost like a calling.

Now she wants us to remember that as long as there are survivors to remember, tragedies continue to echo long after the news photographs and on-the-scene reports have faded. And even without survivors, the facts remain. And so Mindock has made it her mission to bear witness, as centuries of writers, composers, and visual artists have done before.

"Blood Soaked Dresses" begins in Rufina Amaya's voice: "Death crawls underneath this world and waits. Who will be next? Three months ago, the soldiers murdered my two little girls. . . . Their screams were like bad music. . . . I talk to them every morning. . . . At night, they invent my dreams."

Mindock continues her book with the sad indictment that, no matter how high the cost in human suffering, our attention will not be held. We will forget, turn away, move on with our lives. But maybe we can be persuaded to remember, if only for the time it takes to look at a painting. Or read a poem.

El Salvador perspectives

Dec. 11, 2007

Blood Soaked Dresses is a recently published book of poetry by Boston area poet Gloria Mindock. The book was recently reviewed in the Boston Globe:

Every day we wake to newspapers full of new human catastrophes of all types in various places, year after year, decade after decade. Bosnia, Aceh, Sudan, Bhopal blur in our minds into a vague disaster stew. And though we are caring people, we are human and the tragedies are painful. So we ignore. We forget. Unless someone insists on reminding us, as Gloria Mindock does of the civil war that raged in El Salvador from 1980 to 1992. In her new poetry collection, "Blood Soaked Dresses," she holds up the events so we cannot look away...

Now she wants us to remember that as long as there are survivors to remember, tragedies continue to echo long after the news photographs and on-the-scene reports have faded. And even without survivors, the facts remain. And so Mindock has made it her mission to bear witness, as centuries of writers, composers, and visual artists have done before. (more).

Here is one of the poems of bitter memory from the book:

El Salvador, 1983

Somewhere, someone is mourning

for the body of a brilliant one.

Man or woman, it doesn't matter.

The tears in this country, an entrance

to a void . . . shadows touching skin like frost.

A star fell north of this city. Armies parade around

in their uniforms bragging about the killings.

Dead bodies thrown into a pit, cry.

Flesh hits wind, wind hits flesh.

How many dead?

Finally, they are covered with dirt at noon.

All eyelids are closed.

No one knows nothing.

No breathing assaults to hold us. The bitter ash

weeps over the world, and no other country

wants to see it, taste

the dead on their tongue or wipe away all

the weeping.

Dec. 11, 2007

Blood Soaked Dresses is a recently published book of poetry by Boston area poet Gloria Mindock. The book was recently reviewed in the Boston Globe:

Every day we wake to newspapers full of new human catastrophes of all types in various places, year after year, decade after decade. Bosnia, Aceh, Sudan, Bhopal blur in our minds into a vague disaster stew. And though we are caring people, we are human and the tragedies are painful. So we ignore. We forget. Unless someone insists on reminding us, as Gloria Mindock does of the civil war that raged in El Salvador from 1980 to 1992. In her new poetry collection, "Blood Soaked Dresses," she holds up the events so we cannot look away...

Now she wants us to remember that as long as there are survivors to remember, tragedies continue to echo long after the news photographs and on-the-scene reports have faded. And even without survivors, the facts remain. And so Mindock has made it her mission to bear witness, as centuries of writers, composers, and visual artists have done before. (more).

Here is one of the poems of bitter memory from the book:

El Salvador, 1983

Somewhere, someone is mourning

for the body of a brilliant one.

Man or woman, it doesn't matter.

The tears in this country, an entrance

to a void . . . shadows touching skin like frost.

A star fell north of this city. Armies parade around

in their uniforms bragging about the killings.

Dead bodies thrown into a pit, cry.

Flesh hits wind, wind hits flesh.

How many dead?

Finally, they are covered with dirt at noon.

All eyelids are closed.

No one knows nothing.

No breathing assaults to hold us. The bitter ash

weeps over the world, and no other country

wants to see it, taste

the dead on their tongue or wipe away all

the weeping.

Boston Small Press and Poetry Scene

Blood Soaked Dresses (Ibbetson St.) by Gloria Mindock

Reviewed by Lo Galluccio

Wednesday, December 26th, 2007

I was eager to read the entirety of “Blood Soaked Dresses” after hearing Gloria Mindock read several of its poems at the Somerville Writer’s Festival in November. Surprised to hear one friend, a yogi who I would have expected to have a stronger stomach and a willing imagination, declared the poems “too dark.” She left the hall, upon hearing this, I strongly disagree.

“Torment”

Swimming in a stream of nothingness,

there is no line

to grab me.

My speech comes out in a scream.

Must I wrestle with these borrowed dreams?

Convince myself of song?

Do I really have the gift of breath?

Tongue is cursing throat-

Fingers flicker out-

Eyes Desire teeth-

Life of the petrified dead

remind me of my torment.

…

El Salvador is crazy.

It has abandoned me and blessed me

with nightfall.

This work is a complex requiem to war and the death that war bequeaths. One could read the poems, each like a short musical movement or song, and know there is morbidity there, but somehow Gloria also evokes beautiful melodies, laments, echoing patterns of loss. The elegance and metaphysical depths of these poems, often inhabiting a negative space between sky and grave, more than redeems this morbid look at the brutality of wars butchery— its bones, blood, its pain and its terrible attempt to render human life, “nothingness.”

This book is not a journalistic or factual account of the El Salvador Civil War which lasted from approximately 1980-1992. Once the Christian Democratic Party lost control under Jose Napoleon Duarte, there were repeated coups and protest in the early “70’s.” And beginning in 1979-when Duarte was exiled-a cycle of violence and guerilla warfare broke out in the cities and countryside, initiating what became a 12- year civil war. A key signpost for those in the United States, was the murder of the Archbishop of San Salvador, Oscar Romero, after he publicly urged the US government not to provide military support to the El Salvadoran government.

In such a Catholic country, it is only natural that God is invoked as being absent and yet also, in his many forms, a longed for salvation. But there is also an almost dream-like thirst for retribution. In “Archbishop Romero,” she writes:

“Sin has formed on their mouths, and they

assault us.

We are silenced into a void.

Souls singled out for torture.”

“Oscar Romero created a heaven.

carried us in his arms of prayer.

In church, we drink Christ to free ourselves.

Decapitation was not a devotion to believe in.

The soldiers will burn in a red sky.”

The contours of the book follow Gloria’s journey into the massacres and eclipsed lives of the country’s citizens through imagined portraits and its people by capturing the way death can permeate a landscape, while angels and memory and rosaries and love haunt it as well. Her insight and identification with the people of El Salvador, the reveries she channels about the sheer madness of the War, are nothing short of astounding. We walk with her in a shroud of language that gives dignity and concreteness to the way these people surrendered and remained hopeful about their fate at the hands of the death-bearers-soldiers, campesinos, assassins. Yet we still know almost nothing about the logistics and politics of their deaths. In fact one of the key and tragic notes in the mystery which envelopes the war-not unlike many wars fought in small, “developing” or “third world” countries where the United States does not intervene to end violence, or in fact, as in Iraq, has a strong hand in engendering it.

Gloria does not choose to point fingers. She writes to mourn and give voice and magical imagery to the victims. I think it would be correct to say she goes one step farther; she actually becomes the El Salvadoran people caught in a looming death-trap.

The book is dedicated to Rufina Amaya, “the only survivor of the massacre of El Mozote. Gloria writes, “She lived her life speaking about the atrocities committed so no one would forget.” The epigraph reads: But she had so rubbed her eyes from grief that all she had seen could be seen in them.

The book is divided into five sections: The Atrocities, Countryside Thoughts, Hearts, Exile, and Looking Back. In “Waiting for Execution” (from Atrocities) she writes:

“My spirit accelerated into the sky.

The mountains were happy by the sea.

The enemy was not around.

At church, communion was red wine. A sip—I wanted

it all. To drink would make my life last, make me immune.

God of God, this air is hot.

I’m heaving from the stench. These are the bodies

in your hands. How many can you hold?

Will you hold me?

…

The pain waits for an entrance.

If they shoot me, I conquer, and you God

unseen in your cage, cry, escaping from my rusted dreams.”

This book is not about religion, not about God. It is more about angels and their various manifestations. as people, as hearts, as memory. In “Befallen” (Countryside Thoughts) she writes:

“The one last heart to remain in

this world circles around me.

Angel, I have a good perspective about this.

A heart is on my doorstep, and it is haunting,

figuring out who it will go to.

I have courage. The dead love me.”

…

“Angel, I am devoted.

Bury me in your wings.

Enfold me for safe-keeping.

I need to be warm.”

There are many many poems one could quote. Gloria has inscribed many deaths into this book with her soul’s quill and that does make it challenging to read. Yet, like a gorgeous elegy, she also renders these deaths and the unspeakable brutality of their killers, into a kind of otherworldly music we could all find cadence with, and drink in. One other point to be made, “Blood Soaked Dresses” is dedicated to a woman and the dresses could be just as well pants, given the boys who were also murdered, but significant to note that this is a woman’s quilting a shroud of beauty against violence. In an North American world where we are growing more and more habituated to its glamour-in TV and movies-I am thankful for her devotion to life.

—Lo Galluccio

Blood Soaked Dresses (Ibbetson St.) by Gloria Mindock

Reviewed by Lo Galluccio

Wednesday, December 26th, 2007

I was eager to read the entirety of “Blood Soaked Dresses” after hearing Gloria Mindock read several of its poems at the Somerville Writer’s Festival in November. Surprised to hear one friend, a yogi who I would have expected to have a stronger stomach and a willing imagination, declared the poems “too dark.” She left the hall, upon hearing this, I strongly disagree.

“Torment”

Swimming in a stream of nothingness,

there is no line

to grab me.

My speech comes out in a scream.

Must I wrestle with these borrowed dreams?

Convince myself of song?

Do I really have the gift of breath?

Tongue is cursing throat-

Fingers flicker out-

Eyes Desire teeth-

Life of the petrified dead

remind me of my torment.

…

El Salvador is crazy.

It has abandoned me and blessed me

with nightfall.

This work is a complex requiem to war and the death that war bequeaths. One could read the poems, each like a short musical movement or song, and know there is morbidity there, but somehow Gloria also evokes beautiful melodies, laments, echoing patterns of loss. The elegance and metaphysical depths of these poems, often inhabiting a negative space between sky and grave, more than redeems this morbid look at the brutality of wars butchery— its bones, blood, its pain and its terrible attempt to render human life, “nothingness.”

This book is not a journalistic or factual account of the El Salvador Civil War which lasted from approximately 1980-1992. Once the Christian Democratic Party lost control under Jose Napoleon Duarte, there were repeated coups and protest in the early “70’s.” And beginning in 1979-when Duarte was exiled-a cycle of violence and guerilla warfare broke out in the cities and countryside, initiating what became a 12- year civil war. A key signpost for those in the United States, was the murder of the Archbishop of San Salvador, Oscar Romero, after he publicly urged the US government not to provide military support to the El Salvadoran government.

In such a Catholic country, it is only natural that God is invoked as being absent and yet also, in his many forms, a longed for salvation. But there is also an almost dream-like thirst for retribution. In “Archbishop Romero,” she writes:

“Sin has formed on their mouths, and they

assault us.

We are silenced into a void.

Souls singled out for torture.”

“Oscar Romero created a heaven.

carried us in his arms of prayer.

In church, we drink Christ to free ourselves.

Decapitation was not a devotion to believe in.

The soldiers will burn in a red sky.”

The contours of the book follow Gloria’s journey into the massacres and eclipsed lives of the country’s citizens through imagined portraits and its people by capturing the way death can permeate a landscape, while angels and memory and rosaries and love haunt it as well. Her insight and identification with the people of El Salvador, the reveries she channels about the sheer madness of the War, are nothing short of astounding. We walk with her in a shroud of language that gives dignity and concreteness to the way these people surrendered and remained hopeful about their fate at the hands of the death-bearers-soldiers, campesinos, assassins. Yet we still know almost nothing about the logistics and politics of their deaths. In fact one of the key and tragic notes in the mystery which envelopes the war-not unlike many wars fought in small, “developing” or “third world” countries where the United States does not intervene to end violence, or in fact, as in Iraq, has a strong hand in engendering it.

Gloria does not choose to point fingers. She writes to mourn and give voice and magical imagery to the victims. I think it would be correct to say she goes one step farther; she actually becomes the El Salvadoran people caught in a looming death-trap.

The book is dedicated to Rufina Amaya, “the only survivor of the massacre of El Mozote. Gloria writes, “She lived her life speaking about the atrocities committed so no one would forget.” The epigraph reads: But she had so rubbed her eyes from grief that all she had seen could be seen in them.

The book is divided into five sections: The Atrocities, Countryside Thoughts, Hearts, Exile, and Looking Back. In “Waiting for Execution” (from Atrocities) she writes:

“My spirit accelerated into the sky.

The mountains were happy by the sea.

The enemy was not around.

At church, communion was red wine. A sip—I wanted

it all. To drink would make my life last, make me immune.

God of God, this air is hot.

I’m heaving from the stench. These are the bodies

in your hands. How many can you hold?

Will you hold me?

…

The pain waits for an entrance.

If they shoot me, I conquer, and you God

unseen in your cage, cry, escaping from my rusted dreams.”

This book is not about religion, not about God. It is more about angels and their various manifestations. as people, as hearts, as memory. In “Befallen” (Countryside Thoughts) she writes:

“The one last heart to remain in

this world circles around me.

Angel, I have a good perspective about this.

A heart is on my doorstep, and it is haunting,

figuring out who it will go to.

I have courage. The dead love me.”

…

“Angel, I am devoted.

Bury me in your wings.

Enfold me for safe-keeping.

I need to be warm.”

There are many many poems one could quote. Gloria has inscribed many deaths into this book with her soul’s quill and that does make it challenging to read. Yet, like a gorgeous elegy, she also renders these deaths and the unspeakable brutality of their killers, into a kind of otherworldly music we could all find cadence with, and drink in. One other point to be made, “Blood Soaked Dresses” is dedicated to a woman and the dresses could be just as well pants, given the boys who were also murdered, but significant to note that this is a woman’s quilting a shroud of beauty against violence. In an North American world where we are growing more and more habituated to its glamour-in TV and movies-I am thankful for her devotion to life.

—Lo Galluccio

Review by Charles P. Ries

This review appeared in 30 literary journals

In her third book of poetry, “Blood Soaked Dresses” Gloria Mindock raises horror to transcendent allegory. With language that has a lyrical soft quality to it, her new book of poetry becomes the perfect vehicle to express moments (sad, horrific, and glorious) that are set in El Salvador during its civil war from 1980 to 1992. When we see the massacre of innocents continuing in Kenya, Somalia, Darfur, Iraq, Afghanistan – the list becomes painfully endless. Her book becomes a timeless poetic prayer for peace.

Her book of poetry is about the most painful of subjects. Through Mindock’s love of this culture, its people, words, and many flavors, she creates transcendent metaphor after transcendent metaphor. Here are a few cherry-picked from her poem, “Seeing Is Only a Flawed Secret”: “A long shadow filling my body”, “I have conversation with the abyss”; “My weary mind is just a symbol.” “The sky is gray today. / healing itself back to blue.” Jesus, rearrange your schedule. / Go, show me your lips. Make your kiss / a compass so I know where to go.” “I look out the window and feel / like a fool. / Everyone carries on with no ears. / Such motionless supervision – a crime!” Amazing – and these lines and phrases are taken from just one of her 45 poems.

Mindock’s success with “Blood Soaked Dresses” is all the more remarkable given how very hard it is to write about horror. If a poet can enter into this world, speak to this blackness and create a wisp of hope, then the poet is by demonstration a great writer indeed.

-Charles P. Ries

This review appeared in 30 literary journals

In her third book of poetry, “Blood Soaked Dresses” Gloria Mindock raises horror to transcendent allegory. With language that has a lyrical soft quality to it, her new book of poetry becomes the perfect vehicle to express moments (sad, horrific, and glorious) that are set in El Salvador during its civil war from 1980 to 1992. When we see the massacre of innocents continuing in Kenya, Somalia, Darfur, Iraq, Afghanistan – the list becomes painfully endless. Her book becomes a timeless poetic prayer for peace.

Her book of poetry is about the most painful of subjects. Through Mindock’s love of this culture, its people, words, and many flavors, she creates transcendent metaphor after transcendent metaphor. Here are a few cherry-picked from her poem, “Seeing Is Only a Flawed Secret”: “A long shadow filling my body”, “I have conversation with the abyss”; “My weary mind is just a symbol.” “The sky is gray today. / healing itself back to blue.” Jesus, rearrange your schedule. / Go, show me your lips. Make your kiss / a compass so I know where to go.” “I look out the window and feel / like a fool. / Everyone carries on with no ears. / Such motionless supervision – a crime!” Amazing – and these lines and phrases are taken from just one of her 45 poems.

Mindock’s success with “Blood Soaked Dresses” is all the more remarkable given how very hard it is to write about horror. If a poet can enter into this world, speak to this blackness and create a wisp of hope, then the poet is by demonstration a great writer indeed.

-Charles P. Ries

Etkin’s Weekly by Etkin Getir

Wednesday, December 5th, 2007

Istanbul, Turkey

Review: Blood Soaked Dresses

Among the many delicate books I’ve received over past two months, one of them especially drew my interest for a number of reasons.

It was a poetry collection called “Blood Soaked Dresses” by Gloria Mindock, the woman who handles the editorial position of Istanbul Literature Review ever since she took over it. Another reason was the theme of the book- El Salvador Massacre.

In Blood Soaked Dresses, the poet tells the story in five beautiful and well organized chapters:

The Atrocities, Countryside Thoughts, Hearts, Exile and Looking Back. What makes this collection this unique for me is that Gloria is literally living the story as she is telling it. The events on this 62 page-collection frequently give you shivers from up and down your spine and you are always a subject to a set of emotions.

In El Mozote she says:

Bones on the side of the path

are collected, put into sacks.

I want to grab them. Empty them

On the ground and make a pattern.

How many sacks must I have to do this?

This is like playing pick-up sticks.

And she further develops her thoughts in Knife:

I am in pieces.

I close my eyes and cry slowly as

to not flood myself.

On the rear cover, John Minczeski says “A poet must never shy from necessary, no matter how hard it is. In poetry, that is both elegant and brutal, Gloria Mindock exposes the horror of the Salvadoran conflict especially on women…” This is an idea any poetry reader in today’s world should definitely agree with. And that’s what she really mastered in the book.

Back to the poems, as a closing scene, in the final poem Hope she says:

Everything means something to me.

I store my own leaves

of darkness

so do not worry.

Death moves at a incredible speed

but I move faster.

So fast in fact, that the boundaries between us

Can only dream.

Blood Soaked Dresses has a documentary quality. The dreadful events that took place in El Mozote is not something to forget and with these set of poems, the picture grows more vivid than ever in our memories.

A big congratulations to my dear friend Gloria

-Etkin Getir

Wednesday, December 5th, 2007

Istanbul, Turkey

Review: Blood Soaked Dresses

Among the many delicate books I’ve received over past two months, one of them especially drew my interest for a number of reasons.

It was a poetry collection called “Blood Soaked Dresses” by Gloria Mindock, the woman who handles the editorial position of Istanbul Literature Review ever since she took over it. Another reason was the theme of the book- El Salvador Massacre.

In Blood Soaked Dresses, the poet tells the story in five beautiful and well organized chapters:

The Atrocities, Countryside Thoughts, Hearts, Exile and Looking Back. What makes this collection this unique for me is that Gloria is literally living the story as she is telling it. The events on this 62 page-collection frequently give you shivers from up and down your spine and you are always a subject to a set of emotions.

In El Mozote she says:

Bones on the side of the path

are collected, put into sacks.

I want to grab them. Empty them

On the ground and make a pattern.

How many sacks must I have to do this?

This is like playing pick-up sticks.

And she further develops her thoughts in Knife:

I am in pieces.

I close my eyes and cry slowly as

to not flood myself.

On the rear cover, John Minczeski says “A poet must never shy from necessary, no matter how hard it is. In poetry, that is both elegant and brutal, Gloria Mindock exposes the horror of the Salvadoran conflict especially on women…” This is an idea any poetry reader in today’s world should definitely agree with. And that’s what she really mastered in the book.

Back to the poems, as a closing scene, in the final poem Hope she says:

Everything means something to me.

I store my own leaves

of darkness

so do not worry.

Death moves at a incredible speed

but I move faster.

So fast in fact, that the boundaries between us

Can only dream.

Blood Soaked Dresses has a documentary quality. The dreadful events that took place in El Mozote is not something to forget and with these set of poems, the picture grows more vivid than ever in our memories.

A big congratulations to my dear friend Gloria

-Etkin Getir

Reviewed August 7, 2016 by Jeffrey Miller on Amazon

Blood Soaked Dresses

If there was one thing that a poet must do when approaching their craft it would most certainly be never avoiding topics which are too horrific or frightful. To be sure, it is a poet’s responsibility to do just that so we can benefit from one’s analysis and commentary. Whether it’s war, famine, genocide, civil rights, or death, the poets are the ones who shine through the darkness to help us better understand our world and give us all hope.

In Blood Soaked Dresses, Gloria Mindock journeys back in time to the late 1970s and the civil war in El Salvador (1979-1992). She exposes both the atrocities and the horror of this conflict, especially the way that women were affected by it. In hauntingly evocative verse that is brutal and honest, Mindock makes this civil war personal for the readers. These are not just nameless individuals who were killed (one figure places the death toll at over 75,000) or maimed by the conflict; instead, as only a poet can do, she resurrects them and the events of this terrible conflict so we won’t forget. Ultimately, she gives a voice to these tormented souls.

In “El Salvador Bird Watches” she writes about a person waiting to be executed:

“My heart beats so fast into this shallow air.

How can I be heard?

Orange rinds are shoved into my mouth

suffocating me with fragrance. Sadness engulfs me

to know my skin will be stripped and added to the heap.”

Aside from the juxtaposition of the sweet fragrance of orange rinds being stuffed into the person’s mouth to silence the screams, what’s most haunting about this poem is the fact that parakeets flock over the capitol city of San Salvador every day at five in the morning and in the evening and they bear witness to the atrocities happening below.

“The sky is blue, and it’s just another day.”

In that one line, Mindock is brilliant as she compares both the parakeet’s flight and the atrocities below as being a daily occurrence.

And in “Death March” Mindock wonders if the world will remember what happened here and if so, to make sure that those who perished here will never be forgotten:

“Who will be at my funeral?

Who out of this dying world?

A few friends, family, a pair of eyes that loved me

but never told me-

Let us sleep admired.”

These poems are a grim reminder of the evil that exists in our world. These could be poems about other places where hell was in session: Cambodia, Sudan, Rwandan, Syria, and Bosnia. It’s always the poets and the saints who get it right. We should heed their words and listen as if our very own survival depends upon it.

-Jeffrey Miller

Blood Soaked Dresses

If there was one thing that a poet must do when approaching their craft it would most certainly be never avoiding topics which are too horrific or frightful. To be sure, it is a poet’s responsibility to do just that so we can benefit from one’s analysis and commentary. Whether it’s war, famine, genocide, civil rights, or death, the poets are the ones who shine through the darkness to help us better understand our world and give us all hope.

In Blood Soaked Dresses, Gloria Mindock journeys back in time to the late 1970s and the civil war in El Salvador (1979-1992). She exposes both the atrocities and the horror of this conflict, especially the way that women were affected by it. In hauntingly evocative verse that is brutal and honest, Mindock makes this civil war personal for the readers. These are not just nameless individuals who were killed (one figure places the death toll at over 75,000) or maimed by the conflict; instead, as only a poet can do, she resurrects them and the events of this terrible conflict so we won’t forget. Ultimately, she gives a voice to these tormented souls.

In “El Salvador Bird Watches” she writes about a person waiting to be executed:

“My heart beats so fast into this shallow air.

How can I be heard?

Orange rinds are shoved into my mouth

suffocating me with fragrance. Sadness engulfs me

to know my skin will be stripped and added to the heap.”

Aside from the juxtaposition of the sweet fragrance of orange rinds being stuffed into the person’s mouth to silence the screams, what’s most haunting about this poem is the fact that parakeets flock over the capitol city of San Salvador every day at five in the morning and in the evening and they bear witness to the atrocities happening below.

“The sky is blue, and it’s just another day.”

In that one line, Mindock is brilliant as she compares both the parakeet’s flight and the atrocities below as being a daily occurrence.

And in “Death March” Mindock wonders if the world will remember what happened here and if so, to make sure that those who perished here will never be forgotten:

“Who will be at my funeral?

Who out of this dying world?

A few friends, family, a pair of eyes that loved me

but never told me-

Let us sleep admired.”

These poems are a grim reminder of the evil that exists in our world. These could be poems about other places where hell was in session: Cambodia, Sudan, Rwandan, Syria, and Bosnia. It’s always the poets and the saints who get it right. We should heed their words and listen as if our very own survival depends upon it.

-Jeffrey Miller