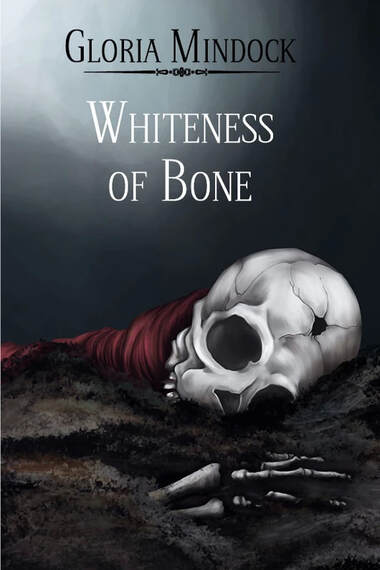

Whiteness of Bone

(Glass Lyre Press, 2016)

GLORIA MINDOCK

Hope and peace is pitted against relentless oppression and death in Gloria Mindock's Whiteness of Bone. Mindock gathers the eye witness accounts of the voiceless, the unheard, and crafts a voice in their stead. From El Salvador to Rwanda, Darfur to the Congo, mass graves and war crimes deafen and suffocate. Genocide is a quagmire of ruthless animal instinct, senseless violence, rape and torture, massacre and slaughter. When such darkness goes ignored, the gaping maw of the abyss grows ever larger still. Victims of war escape only to be confronted by the merciless apathy of the world. Survival is an exercise in learned helplessness. Mere existence is not living. The gutted and the mute fall silent. Yet what can poetry do?

It is language when there are no adequate words. It is urgency, immediacy, and testimony. It is how compassion and empathy can pour themselves into the confines of silence and fill it up instead. When there is simply no explanation left for catastrophe and horror, it is poetry that can capture and cradle the souls of those decaying in fields of white bone.

(Glass Lyre Press, 2016)

GLORIA MINDOCK

Hope and peace is pitted against relentless oppression and death in Gloria Mindock's Whiteness of Bone. Mindock gathers the eye witness accounts of the voiceless, the unheard, and crafts a voice in their stead. From El Salvador to Rwanda, Darfur to the Congo, mass graves and war crimes deafen and suffocate. Genocide is a quagmire of ruthless animal instinct, senseless violence, rape and torture, massacre and slaughter. When such darkness goes ignored, the gaping maw of the abyss grows ever larger still. Victims of war escape only to be confronted by the merciless apathy of the world. Survival is an exercise in learned helplessness. Mere existence is not living. The gutted and the mute fall silent. Yet what can poetry do?

It is language when there are no adequate words. It is urgency, immediacy, and testimony. It is how compassion and empathy can pour themselves into the confines of silence and fill it up instead. When there is simply no explanation left for catastrophe and horror, it is poetry that can capture and cradle the souls of those decaying in fields of white bone.

Regular price $16.00

More Rave Reviews for Whiteness Of Bone

Pedestal Magazine

Reviewer: Lynn Levin

Political poetry is necessary poetry, but it is also one of the most difficult types of poetry to write. The moral imperative that drives poems of outrage against man’s inhumanity to man often leads to work that explodes with fury and gore. How to capture on the page the massacres, beatings, tortures, and schemes of dictators and warlords? To what extent is the description of atrocity the mission of political poets? To what extent should political poetry use the violence as a backdrop, focusing instead on the lives of individuals—the victims, partisans, even the perpetrators—caught in the storm? And, finally, how is one to make art out of agony and destruction? In her newest collection, Whiteness of Bone, Gloria Mindock assigns herself the difficult mission of being a political poet.

The founding editor of Červená Barva, a Boston-area press well known for its strong international and US list of contemporary poetry and prose, Mindock is the author of several books of poetry, some of them published in translation. She is the recipient of the Ibbetson Street Press Lifetime Achievement Award and the Allen Ginsberg Award from the Newton Writing and Publishing Center for her community service.

In Whiteness of Bone, Mindock bravely confronts some of the genocides and bloodiest political conflicts of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries: the catastrophes of El Salvador, Rwanda, the Congo, and Darfur. In order to gather material and details for the poems, the author corresponded directly with a number of survivors from these regions. This research allows Mindock to bear witness, albeit indirectly, and to describe in poetry what the survivors themselves may not be able to do.

The strongest poems in the collection engage violence through specific individual situations or voices. The lyric “Eye (Mistranslation from a Romanian Poem)” does not name a country or conflict, but it conveys anger in an emotionally intimate manner. The voice is engagingly unadorned:

If you can see the pupil in my eye, know it is an instrument

of sight, pinning its gaze on you.

I did not carry an umbrella on this rainy day,

but I will tell you one thing, you are an insensitive bastard.

Apparently, no one told you.

Well, I am the plant in the system to let you know.

Your rage has been defeated.

The volume in your mind knocked out in an instant.

Let me make this clear.

Your soul is a never-ending circle bruising itself

to black and blue.

The invective in this poem is spirited. The community has suffered and survived, and the poem ends on a hopeful note as the children who outlived the conflict ready themselves for a better future.

Midway through the collection, Mindock focuses on the Salvadoran Civil War, which mostly took place during the 1980s. I found the biographical poem “Maria” to be exceptionally gripping. Here Mindock describes some of the life journey of a nine-year-old girl whose mother was killed by a death squad. The child crawls into the mass grave in which her mother lies, embraces her corpse, tears off a piece of the mother’s clothing to save as a keepsake, and recalls, through Mindock’s touching third-person narration, their life together:

See her smile as you cooked supper together.

Hear her laugh as you played.

Hear her tell you not to wander too far away.

All these things a mother does.

The cloth now pressed close to you.

Ultimately, Maria is saved by another family and brought to Illinois where she grew up safe and well cared for. She now travels the world bearing witness to suffering in her homeland.

In political poetry, the urge to describe and condemn atrocities often conflicts with the poetic imperative to write in unusual, evocative, and even appealing language. Mindock addresses this issue in the poem “Don’t.” “Don’t tell me my writing is too graphic / for you as you sit in your nice apartment / enjoying the day, sleeping peacefully at night.” Well, perhaps at times the poems are too graphic. Or rather, they occasionally overly reiterate the horrors of bloody tribal, political, sectarian, and factional warfare, bludgeoning a reader into a kind of defensive numbness rather than a heightened awareness. That said, most of the poems add to rather than detract from an overall effect, and are threaded with captivating lines. For example in “Tongue,” a victim of torture speaks:

My lips hurt and they’re on fire.

I look at them and pretend my

body is a vase, full of flowers-

transforming into spring blossoms.

In “Dante,” I find this standout line: “Time moves, collecting death for its museums.” I admire the opening lines in “Adventure”: “The rain hits the earth / with such force, soaking the ground, / cleaning it up for its next adventure.” These lines in “Strength” also moved me:

When shadows fell on my heart,

I became fulfilled.

Now, I have felt everything

there is to feel.

That said, in these poems, as in a few others, some lines devolve, as mentioned above, into excessive references to machetes, bullets, blood, silenced voices, and graves. The collection might have benefited from a few more allusions to love, hope, and relief. Yet the mission of this collection is to capture the awful repetitiveness of war, genocides, tortures, and massacres. This is human history at its worst. And a poet, even one as principled as Gloria Mindock, is aware that, though she speaks out, she is ultimately powerless to halt the onslaught. She writes. She documents. She knows that her work may never make a difference in the larger sense. As Auden wrote in his elegy, “In Memory of W. B. Yeats”:

For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives

In the valley of its making where executives

Would never want to tamper, flows on south

From ranches of isolation and the busy griefs,

Raw towns that we believe and die in; it survives,

A way of happening, a mouth.

And still, the poet writes and hopes. And still we read.

Reviewer: Lynn Levin

Political poetry is necessary poetry, but it is also one of the most difficult types of poetry to write. The moral imperative that drives poems of outrage against man’s inhumanity to man often leads to work that explodes with fury and gore. How to capture on the page the massacres, beatings, tortures, and schemes of dictators and warlords? To what extent is the description of atrocity the mission of political poets? To what extent should political poetry use the violence as a backdrop, focusing instead on the lives of individuals—the victims, partisans, even the perpetrators—caught in the storm? And, finally, how is one to make art out of agony and destruction? In her newest collection, Whiteness of Bone, Gloria Mindock assigns herself the difficult mission of being a political poet.

The founding editor of Červená Barva, a Boston-area press well known for its strong international and US list of contemporary poetry and prose, Mindock is the author of several books of poetry, some of them published in translation. She is the recipient of the Ibbetson Street Press Lifetime Achievement Award and the Allen Ginsberg Award from the Newton Writing and Publishing Center for her community service.

In Whiteness of Bone, Mindock bravely confronts some of the genocides and bloodiest political conflicts of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries: the catastrophes of El Salvador, Rwanda, the Congo, and Darfur. In order to gather material and details for the poems, the author corresponded directly with a number of survivors from these regions. This research allows Mindock to bear witness, albeit indirectly, and to describe in poetry what the survivors themselves may not be able to do.

The strongest poems in the collection engage violence through specific individual situations or voices. The lyric “Eye (Mistranslation from a Romanian Poem)” does not name a country or conflict, but it conveys anger in an emotionally intimate manner. The voice is engagingly unadorned:

If you can see the pupil in my eye, know it is an instrument

of sight, pinning its gaze on you.

I did not carry an umbrella on this rainy day,

but I will tell you one thing, you are an insensitive bastard.

Apparently, no one told you.

Well, I am the plant in the system to let you know.

Your rage has been defeated.

The volume in your mind knocked out in an instant.

Let me make this clear.

Your soul is a never-ending circle bruising itself

to black and blue.

The invective in this poem is spirited. The community has suffered and survived, and the poem ends on a hopeful note as the children who outlived the conflict ready themselves for a better future.

Midway through the collection, Mindock focuses on the Salvadoran Civil War, which mostly took place during the 1980s. I found the biographical poem “Maria” to be exceptionally gripping. Here Mindock describes some of the life journey of a nine-year-old girl whose mother was killed by a death squad. The child crawls into the mass grave in which her mother lies, embraces her corpse, tears off a piece of the mother’s clothing to save as a keepsake, and recalls, through Mindock’s touching third-person narration, their life together:

See her smile as you cooked supper together.

Hear her laugh as you played.

Hear her tell you not to wander too far away.

All these things a mother does.

The cloth now pressed close to you.

Ultimately, Maria is saved by another family and brought to Illinois where she grew up safe and well cared for. She now travels the world bearing witness to suffering in her homeland.

In political poetry, the urge to describe and condemn atrocities often conflicts with the poetic imperative to write in unusual, evocative, and even appealing language. Mindock addresses this issue in the poem “Don’t.” “Don’t tell me my writing is too graphic / for you as you sit in your nice apartment / enjoying the day, sleeping peacefully at night.” Well, perhaps at times the poems are too graphic. Or rather, they occasionally overly reiterate the horrors of bloody tribal, political, sectarian, and factional warfare, bludgeoning a reader into a kind of defensive numbness rather than a heightened awareness. That said, most of the poems add to rather than detract from an overall effect, and are threaded with captivating lines. For example in “Tongue,” a victim of torture speaks:

My lips hurt and they’re on fire.

I look at them and pretend my

body is a vase, full of flowers-

transforming into spring blossoms.

In “Dante,” I find this standout line: “Time moves, collecting death for its museums.” I admire the opening lines in “Adventure”: “The rain hits the earth / with such force, soaking the ground, / cleaning it up for its next adventure.” These lines in “Strength” also moved me:

When shadows fell on my heart,

I became fulfilled.

Now, I have felt everything

there is to feel.

That said, in these poems, as in a few others, some lines devolve, as mentioned above, into excessive references to machetes, bullets, blood, silenced voices, and graves. The collection might have benefited from a few more allusions to love, hope, and relief. Yet the mission of this collection is to capture the awful repetitiveness of war, genocides, tortures, and massacres. This is human history at its worst. And a poet, even one as principled as Gloria Mindock, is aware that, though she speaks out, she is ultimately powerless to halt the onslaught. She writes. She documents. She knows that her work may never make a difference in the larger sense. As Auden wrote in his elegy, “In Memory of W. B. Yeats”:

For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives

In the valley of its making where executives

Would never want to tamper, flows on south

From ranches of isolation and the busy griefs,

Raw towns that we believe and die in; it survives,

A way of happening, a mouth.

And still, the poet writes and hopes. And still we read.

Whiteness of Bone is a solid collection of poems, 70 pages, but in essence this represents one longer poem, long weapon piercing human conscience. This is Gloria’s unusual ability to comment on horror. She departed from her earlier more descriptive writings, specific stories and situations to a pure palpable feeling of pain, i.e. direction from the “Art” to Whiteness of Bone. Unlike her own and some other poets’ strong commentary on unfairness and pain in this world in this collection author deals with the subject more directly. Not so much telling the story but dealing with psychophysiology of cruelty and pain. In this respect when we are looking at Francisco Goya’s The Disasters of War we don’t have to know specifically the circumstances of the conflict. We are dealing with them in a biblical sense.

Yes, author names some hot bleeding points on the map of the world: Guatemala, Cambodia, El Salvador, and Rwanda, but here they are as a more of artistic method, than, a set for the specific description.

Most importantly, Gloria manages to render to a reader feeling that this is happening with all of us. For her there is no THEM, it is always US, it is happening to US.

The language of poems is stark, clear, strong, and effective.

-Andrey Gritsman (New York), author of LIVE LANDSCAPE, Editor-in-Chief INTERPOEZIA Magazine, curator of INTERCULTURAL SERIES in New York.

Yes, author names some hot bleeding points on the map of the world: Guatemala, Cambodia, El Salvador, and Rwanda, but here they are as a more of artistic method, than, a set for the specific description.

Most importantly, Gloria manages to render to a reader feeling that this is happening with all of us. For her there is no THEM, it is always US, it is happening to US.

The language of poems is stark, clear, strong, and effective.

-Andrey Gritsman (New York), author of LIVE LANDSCAPE, Editor-in-Chief INTERPOEZIA Magazine, curator of INTERCULTURAL SERIES in New York.

"The air is thin, the silence is deep, and the sun shines relentlessly in

Whiteness of Bone. Gloria Mindock's beautiful, terrible sleepless world, where razor-sharp

verbs and stark nouns invoke both the horror and hope of, and in, life

and death."

-Alexander Motyl, author of Sweet Snow

Whiteness of Bone. Gloria Mindock's beautiful, terrible sleepless world, where razor-sharp

verbs and stark nouns invoke both the horror and hope of, and in, life

and death."

-Alexander Motyl, author of Sweet Snow

TUCK MAGAZINE - Online political, human rights and arts magazine

The Dual “Road” Allegory of Gloria Mindock by Alisa Velaj

December 31, 2018 /Book Reviews , Poetry , POETRY / FICTION

In a handful of Gloria Mindock‘s poems, a “road” allegory comes to shape from two vectors that, upon a first textual read, appear to be opposites. However, both actually head towards the same Ithaca for a destination.

“Love is an ode you owe yourself/— walk down the street and the road will follow” (Adventure)

People know of roads they follow. The poetess, instead, conversely evokes roads that follow people. Meaning, not having human beings seek for a path, but having a path seek for human beings. Loss of direction is common in both cases. A quote from Biblical scriptures uncovers probably the most allegorical verse throughout the New Testament: Jesus answered, “I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me. (John 14:6, Holy Bible, New International Version). It’s the allegory of the right path to take, the path of truth leading to a life of virtue. Jesus speaks of souls bereft of paths; Mindock depicts paths bereft of souls.

Again, as aforementioned, loss of direction is the common derivative. What, then, is the pathway out of such chaos? “Love is an ode you owe yourself”, Mindock replies. One’s search – for roads to follow or to be followed by – requires clarity and patience. Otherwise, the search turns into an adventure prone to surprises, along which ambiguity leads to absurd directions, impatience breeds short-sighted idolatry. In her poem “Déjà Vu”, the poetess assumes a prophetic role as she questions:

Is this a sign, I should be opening doors/ with blind devotion?

Together, love and clear commitment both embrace truth, precisely the truth that pounds the bells on the worldwide tragic reality these days. Unnecessary wars somewhere far from someone’s yard fence; maimed children who today are someone else’s, but tomorrow may well be yours, mine. Ours, above all. We adults, the poetess insists, should learn how to see and, on a parallel level, teach the same to our children. Before it is too late. Before today’s children, likely due to lack of such instruction, do inflict new dramas on tomorrow’s children.

“Such emptiness will cause blindness. /Will you teach them to see?/ […] Most of all, will you teach them to sing?” (Melody)

The poetess invokes the times of grace, or of that gift which mortals are bestowed by faith. We – the offspring of heavenly and earthly love, we – the heartless inventors of wars and destruction, should be grateful for experiencing grace or, as described in the Bible, the experience of receiving gifts not by merit, but by God’s love and will to thus reward our redemption.

“Looking closely, a face is revealed to me,/a brief moment of clarity happens./God is rising into the air with hand reaching out to the plane./Such grace awakens the earth if you look./For most in this world, it is too late” (The Alps)

“If you look” is a straight shot at the capacity to fathom grace, so as to avoid total destruction, because right now “for most in this world, it is too late”. In this respect, Follow the road and/or Be the road stand out as two transcendent credos in Gloria Mindock’s poetry. A pair of twins, seemingly, yet each so unmistakably distinct in their individual identity and personality.

The Dual “Road” Allegory of Gloria Mindock by Alisa Velaj

December 31, 2018 /Book Reviews , Poetry , POETRY / FICTION

In a handful of Gloria Mindock‘s poems, a “road” allegory comes to shape from two vectors that, upon a first textual read, appear to be opposites. However, both actually head towards the same Ithaca for a destination.

“Love is an ode you owe yourself/— walk down the street and the road will follow” (Adventure)

People know of roads they follow. The poetess, instead, conversely evokes roads that follow people. Meaning, not having human beings seek for a path, but having a path seek for human beings. Loss of direction is common in both cases. A quote from Biblical scriptures uncovers probably the most allegorical verse throughout the New Testament: Jesus answered, “I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me. (John 14:6, Holy Bible, New International Version). It’s the allegory of the right path to take, the path of truth leading to a life of virtue. Jesus speaks of souls bereft of paths; Mindock depicts paths bereft of souls.

Again, as aforementioned, loss of direction is the common derivative. What, then, is the pathway out of such chaos? “Love is an ode you owe yourself”, Mindock replies. One’s search – for roads to follow or to be followed by – requires clarity and patience. Otherwise, the search turns into an adventure prone to surprises, along which ambiguity leads to absurd directions, impatience breeds short-sighted idolatry. In her poem “Déjà Vu”, the poetess assumes a prophetic role as she questions:

Is this a sign, I should be opening doors/ with blind devotion?

Together, love and clear commitment both embrace truth, precisely the truth that pounds the bells on the worldwide tragic reality these days. Unnecessary wars somewhere far from someone’s yard fence; maimed children who today are someone else’s, but tomorrow may well be yours, mine. Ours, above all. We adults, the poetess insists, should learn how to see and, on a parallel level, teach the same to our children. Before it is too late. Before today’s children, likely due to lack of such instruction, do inflict new dramas on tomorrow’s children.

“Such emptiness will cause blindness. /Will you teach them to see?/ […] Most of all, will you teach them to sing?” (Melody)

The poetess invokes the times of grace, or of that gift which mortals are bestowed by faith. We – the offspring of heavenly and earthly love, we – the heartless inventors of wars and destruction, should be grateful for experiencing grace or, as described in the Bible, the experience of receiving gifts not by merit, but by God’s love and will to thus reward our redemption.

“Looking closely, a face is revealed to me,/a brief moment of clarity happens./God is rising into the air with hand reaching out to the plane./Such grace awakens the earth if you look./For most in this world, it is too late” (The Alps)

“If you look” is a straight shot at the capacity to fathom grace, so as to avoid total destruction, because right now “for most in this world, it is too late”. In this respect, Follow the road and/or Be the road stand out as two transcendent credos in Gloria Mindock’s poetry. A pair of twins, seemingly, yet each so unmistakably distinct in their individual identity and personality.

Whiteness Of Bone /Amazon reviews

An Amazing Unflinching Look At What Remains

August 21, 2016

Gloria Mindock provides an amazing, unflinching look at the cruel effects brought by the powerful against the "other" all over this planet. Usually hidden from mainstream press accounts and relegated to footnotes in history books, few people realize that even now, especially now, these terrible crimes against humanity continue unabated all over the planet. And such blatant cruelty is fueled by greed and lust for power. Driven by international arms merchants, these atrocities continue, even as we turn away from it. I have read and reread the poetry in Whiteness of Bone and each time I am powerfully affected by the images of the destruction of innocents by those who deny humanity in those "others." I cry for those beautiful lives whose bones and broken bodies remain to tell their stories. This is a brave book of poetry. I am going to buy additional copies of this book to share with others who need to think deeply about these issues. Add it to your bookshelf and share with others.

-Fiction Fan

August 21, 2016

Gloria Mindock provides an amazing, unflinching look at the cruel effects brought by the powerful against the "other" all over this planet. Usually hidden from mainstream press accounts and relegated to footnotes in history books, few people realize that even now, especially now, these terrible crimes against humanity continue unabated all over the planet. And such blatant cruelty is fueled by greed and lust for power. Driven by international arms merchants, these atrocities continue, even as we turn away from it. I have read and reread the poetry in Whiteness of Bone and each time I am powerfully affected by the images of the destruction of innocents by those who deny humanity in those "others." I cry for those beautiful lives whose bones and broken bodies remain to tell their stories. This is a brave book of poetry. I am going to buy additional copies of this book to share with others who need to think deeply about these issues. Add it to your bookshelf and share with others.

-Fiction Fan

A Book We Should All Read

July 16, 2016

Like “a light in a dark world “this new collection of poems WHITENESS OF BONE by Gloria Mindock shines and speaks powerfully to injustice and horror in our time. Atrocities may happen in other countries such as in El Salvador, Rwanda and Darfur, but oppression and suffering anywhere affronts our common bond of humanity. Immensely readable and with urgency, these poems rouse and speak clearly to our human conscience.

-Pui Ying Wong

July 16, 2016

Like “a light in a dark world “this new collection of poems WHITENESS OF BONE by Gloria Mindock shines and speaks powerfully to injustice and horror in our time. Atrocities may happen in other countries such as in El Salvador, Rwanda and Darfur, but oppression and suffering anywhere affronts our common bond of humanity. Immensely readable and with urgency, these poems rouse and speak clearly to our human conscience.

-Pui Ying Wong

A Testament for Us All

August 10, 2016

Gloria Mindock has given the world a witness to the vagaries of war with her collection the Whiteness of Bone. These carefully crafted poems are brutally honest, heartbreakingly poignant and stark in their bedrock of truth. These are poems that bear witness to the strife that touches places near and far, resulting in death, destruction and bloodshed. Mindock's compassion is apparent; her words a testament for us all.

-Michelle M. Reale

August 10, 2016

Gloria Mindock has given the world a witness to the vagaries of war with her collection the Whiteness of Bone. These carefully crafted poems are brutally honest, heartbreakingly poignant and stark in their bedrock of truth. These are poems that bear witness to the strife that touches places near and far, resulting in death, destruction and bloodshed. Mindock's compassion is apparent; her words a testament for us all.

-Michelle M. Reale

August 21, 2016

The speaker in these poems is full of love and compassion but sees the world for what it is. In this truth, wonderful poetry is revealed. Whiteness of Bone is a must read!

-Roberto Carlos Garcia

The speaker in these poems is full of love and compassion but sees the world for what it is. In this truth, wonderful poetry is revealed. Whiteness of Bone is a must read!

-Roberto Carlos Garcia

Beautiful, sad, and powerful

April 10, 2020

Courage and tragedy collide in this powerfully written collection of poems based on the poet's personal correspondences with victims of oppression and genocide in El Salvador, Rwanda, Darfur, and the Congo ("I have been investigating the hearts of the mournful"). These poems serve as their voice - of suffering, of survival, of death ("shot in the head or hacked") - but also to the growing awareness on the part of the poet herself: how deeply she appreciates her freedom and her options as she studies a menu ("How lucky I am when others are not.") Mindock shines with her ability to portray the unspeakable horror ("Women are raped, clothes taken, left to die in their nakedness") while at the same time, offering hope for redemption ("Don't worry, you left footprints on the soil / Stones were set on your grave / to form shapes. / Something to make you smile as you / go on to a new path, a new canvass.") This is a book that demands to be read, over and over.

-Robin Stratton

April 10, 2020

Courage and tragedy collide in this powerfully written collection of poems based on the poet's personal correspondences with victims of oppression and genocide in El Salvador, Rwanda, Darfur, and the Congo ("I have been investigating the hearts of the mournful"). These poems serve as their voice - of suffering, of survival, of death ("shot in the head or hacked") - but also to the growing awareness on the part of the poet herself: how deeply she appreciates her freedom and her options as she studies a menu ("How lucky I am when others are not.") Mindock shines with her ability to portray the unspeakable horror ("Women are raped, clothes taken, left to die in their nakedness") while at the same time, offering hope for redemption ("Don't worry, you left footprints on the soil / Stones were set on your grave / to form shapes. / Something to make you smile as you / go on to a new path, a new canvass.") This is a book that demands to be read, over and over.

-Robin Stratton

Haunting and Evocative

February 5, 2017

If there’s one thing that poetry gives us over other art forms, it would have to be the power in the brevity of language to articulate a spectrum of emotions.

Reading Gloria Mindock’s powerful and moving collection of poetry, Whiteness of Bone, one feels a gamut of emotions as Ms. Mindock documents some of life’s more horrible experiences. To be sure, there’s no other way that a writer could deftly write about the unfairness, pain, and suffering in life the way that she does in her poetry. Never does one feel that she is lecturing to us, telling us what we should feel or do. Instead, like a painter or photographer, she captures the pain and suffering that allows to be moved without any authorial intrusion or commentary. All we have to do is just read one of the poems in this collection, and Mindock’s purpose comes through loud and clear.

For example, in “Don’t,” Mindock asks readers not to question why she writes about the horrors of the world. “It could be you. But it is not./Imagine what it would be like to have your son killed or your daughter taken,/or see your children with no legs?” She just asks readers to imagine what it would be like; that’s all. But in those two short sentences and longer sentence, she conveys not just the horror of what it must be like for parents who have lost a child in a war-torn country or other tragedy but also plants this image in our minds that help us to comprehend unspeakable horrors and atrocities.

One of my personal favorites is “Somewhere” in which Mindock repeats the word “somewhere” at the end of each line (and all in capital letters) as if to say that for most of the world, the pain and suffering is somewhere else and therefore something that doesn’t intrude on our lives. It’s a brilliant and powerful poem in its succinctness and terse choice of words:

“In the photograph, warships

Racing to go SOMEWHERE

Sailors fire missiles SOMEWHERE

Bodies pile up SOMEWHERE

Weeping SOMEWHERE

Anger SOMEWHERE

Injured SOMEWHERE

Blood SOMEWHERE

Seeping into the earth SOMEWHERE….”

In one of the more powerful and haunting poems in this collection, “Whiteness of Bone,” I was reminded of a trip I took to Cambodia in 2006 when I visited a temple outside of Siem Reap that had on display a glass-enclosed structure filled with human skulls. As I stood there, staring at those sun-bleached skulls, it was hard to even begin to fathom the horrors of the genocide which took place in that country. Mindock’s poem does:

“Bones pushing out of bodies, filleted into

whiteness, brutal.

The dead are on a different journey with worn-out hearts.

How much can I say or do to stop this?

No one pays attention in this world.

Suffering has been here since the beginning:

shimmering, drifting, whispering, screaming, crying,

filling the void between peace and death.

All the bones saturate the ground.

One can learn about the life and death of the

dead by holding them.

I hear you, know you, there is no vacancy

in my heart as your life closes in.

The whiteness of bone, I caress, kiss and

retrieve your memories for a better life.”

Powerful and evocative are not strong enough words to describe this collection, but for now, they will have to do. Mindock has given a voice to the pain and suffering in the world, and we should all take notice and listen to what she has to say.

-Jeffrey Miller

February 5, 2017

If there’s one thing that poetry gives us over other art forms, it would have to be the power in the brevity of language to articulate a spectrum of emotions.

Reading Gloria Mindock’s powerful and moving collection of poetry, Whiteness of Bone, one feels a gamut of emotions as Ms. Mindock documents some of life’s more horrible experiences. To be sure, there’s no other way that a writer could deftly write about the unfairness, pain, and suffering in life the way that she does in her poetry. Never does one feel that she is lecturing to us, telling us what we should feel or do. Instead, like a painter or photographer, she captures the pain and suffering that allows to be moved without any authorial intrusion or commentary. All we have to do is just read one of the poems in this collection, and Mindock’s purpose comes through loud and clear.

For example, in “Don’t,” Mindock asks readers not to question why she writes about the horrors of the world. “It could be you. But it is not./Imagine what it would be like to have your son killed or your daughter taken,/or see your children with no legs?” She just asks readers to imagine what it would be like; that’s all. But in those two short sentences and longer sentence, she conveys not just the horror of what it must be like for parents who have lost a child in a war-torn country or other tragedy but also plants this image in our minds that help us to comprehend unspeakable horrors and atrocities.

One of my personal favorites is “Somewhere” in which Mindock repeats the word “somewhere” at the end of each line (and all in capital letters) as if to say that for most of the world, the pain and suffering is somewhere else and therefore something that doesn’t intrude on our lives. It’s a brilliant and powerful poem in its succinctness and terse choice of words:

“In the photograph, warships

Racing to go SOMEWHERE

Sailors fire missiles SOMEWHERE

Bodies pile up SOMEWHERE

Weeping SOMEWHERE

Anger SOMEWHERE

Injured SOMEWHERE

Blood SOMEWHERE

Seeping into the earth SOMEWHERE….”

In one of the more powerful and haunting poems in this collection, “Whiteness of Bone,” I was reminded of a trip I took to Cambodia in 2006 when I visited a temple outside of Siem Reap that had on display a glass-enclosed structure filled with human skulls. As I stood there, staring at those sun-bleached skulls, it was hard to even begin to fathom the horrors of the genocide which took place in that country. Mindock’s poem does:

“Bones pushing out of bodies, filleted into

whiteness, brutal.

The dead are on a different journey with worn-out hearts.

How much can I say or do to stop this?

No one pays attention in this world.

Suffering has been here since the beginning:

shimmering, drifting, whispering, screaming, crying,

filling the void between peace and death.

All the bones saturate the ground.

One can learn about the life and death of the

dead by holding them.

I hear you, know you, there is no vacancy

in my heart as your life closes in.

The whiteness of bone, I caress, kiss and

retrieve your memories for a better life.”

Powerful and evocative are not strong enough words to describe this collection, but for now, they will have to do. Mindock has given a voice to the pain and suffering in the world, and we should all take notice and listen to what she has to say.

-Jeffrey Miller

A Tribute to Morality and Conscience

July 20, 2016

How does a poet express the horrors of genocide without creating a book that is a generalized bloodbath? Poet Gloria Mindock presents her poems in almost a whisper. They are prayers to the dead, and to those so severely damaged from these holocausts that it is difficult to imagine how they continue to endure life. Mindock is a voice for the unheard millions who suffer these deaths, tortures, rapes, and other unimaginable horrors. She speaks for them with a reverence that reaches deep inside the core of the reader. From EYE: "If you can see the pupil in my eye, know it is an instrument / of sight, pinning its gaze on you. /..." From her poem KILL: "The Janjaweed attacked the village, / raped the women out in the open, and / took their clothes./..." And Mindock shares herself in a most tender way without guile: From her poem ORCHESTRA: "I don't think I understand who I am-- / Bohemian girl who never sleeps... / Can I speak to you about my poetry?.../" This is fierce writing with powerful ending lines that sneak up on the reader. WHITENESS OF BONE is a tribute to morality and conscience, and to all who care enough about the disenfranchised people of the world to do something to make change. Most highly recommended.

-Susan Tepper

July 20, 2016

How does a poet express the horrors of genocide without creating a book that is a generalized bloodbath? Poet Gloria Mindock presents her poems in almost a whisper. They are prayers to the dead, and to those so severely damaged from these holocausts that it is difficult to imagine how they continue to endure life. Mindock is a voice for the unheard millions who suffer these deaths, tortures, rapes, and other unimaginable horrors. She speaks for them with a reverence that reaches deep inside the core of the reader. From EYE: "If you can see the pupil in my eye, know it is an instrument / of sight, pinning its gaze on you. /..." From her poem KILL: "The Janjaweed attacked the village, / raped the women out in the open, and / took their clothes./..." And Mindock shares herself in a most tender way without guile: From her poem ORCHESTRA: "I don't think I understand who I am-- / Bohemian girl who never sleeps... / Can I speak to you about my poetry?.../" This is fierce writing with powerful ending lines that sneak up on the reader. WHITENESS OF BONE is a tribute to morality and conscience, and to all who care enough about the disenfranchised people of the world to do something to make change. Most highly recommended.

-Susan Tepper

A Passionate Hymn to the Millions Who Died

October 6, 2016

It may be hard to “speak truth to power,” but it’s far harder to speak truth to horror. What does one say in the face of inexplicable cruelty, the endless slaughters of the innocent that haunt our long and gory history as humans?

Poet Gloria Mindock accomplishes this in her latest poetry offering, "WHITENESS OF BONE.” This 80-page book (no slim volume) is a hymn to the millions slaughtered by the killings in El Salvador, Rwanda, Darfur, and the Congo, giving voice to those who can no longer speak.

It is chilling, yet compelling. As I read, I began to feel that each new poem I saw as I turned the page was yet another victim about to tell me their story. At one point, the actual shape of the words on the page took on the shape of the body of one who had died.

The poems do not speak; they confide, sharing a terrible secret (lean in, you may not hear what I’m saying, no, lean closer, this is important). One is forced to not only hear of the singular terror of each victim but confront it, the brutal aloneness of their deaths, and hear them scream the universal cry of “WHY?”

In one poem, a victim killed with a machete in Rwanda declares,

“Abandoned and lost,

I saw night.”

She could have been describing her book. One does see “night,” but the reader is not abandoned, and certainly not lost.

Highly recommended.

-Martin Golan

October 6, 2016

It may be hard to “speak truth to power,” but it’s far harder to speak truth to horror. What does one say in the face of inexplicable cruelty, the endless slaughters of the innocent that haunt our long and gory history as humans?

Poet Gloria Mindock accomplishes this in her latest poetry offering, "WHITENESS OF BONE.” This 80-page book (no slim volume) is a hymn to the millions slaughtered by the killings in El Salvador, Rwanda, Darfur, and the Congo, giving voice to those who can no longer speak.

It is chilling, yet compelling. As I read, I began to feel that each new poem I saw as I turned the page was yet another victim about to tell me their story. At one point, the actual shape of the words on the page took on the shape of the body of one who had died.

The poems do not speak; they confide, sharing a terrible secret (lean in, you may not hear what I’m saying, no, lean closer, this is important). One is forced to not only hear of the singular terror of each victim but confront it, the brutal aloneness of their deaths, and hear them scream the universal cry of “WHY?”

In one poem, a victim killed with a machete in Rwanda declares,

“Abandoned and lost,

I saw night.”

She could have been describing her book. One does see “night,” but the reader is not abandoned, and certainly not lost.

Highly recommended.

-Martin Golan

Powerful Light from Darkness

August 5, 2016

This is a poet with a deeply felt sensibility for the human condition. Her verse is taut, vibrant, and compelling. She agonizes over the unfeeling and callous manner in which people behave to one another and she expresses her pain in perfectly chosen words and images. It all amounts to a powerfully dark but bittersweet word symphony. This book will stay with the reader a very long time . . . and it should.

-Gunther Purdue

August 5, 2016

This is a poet with a deeply felt sensibility for the human condition. Her verse is taut, vibrant, and compelling. She agonizes over the unfeeling and callous manner in which people behave to one another and she expresses her pain in perfectly chosen words and images. It all amounts to a powerfully dark but bittersweet word symphony. This book will stay with the reader a very long time . . . and it should.

-Gunther Purdue

Beautiful and Intense

February 11, 2017

These poems are as beautiful as they are intense. It leaves you a bit breathless, from both the beauty of the lines and the horror depicted of our world. I imagined holding elegant glass sculptures and turning them around in my hands only to momentarily realize that the edges were all sharp as razors and I was bleeding. Wonderful writing, on both levels.

-D.S. Atkinson

February 11, 2017

These poems are as beautiful as they are intense. It leaves you a bit breathless, from both the beauty of the lines and the horror depicted of our world. I imagined holding elegant glass sculptures and turning them around in my hands only to momentarily realize that the edges were all sharp as razors and I was bleeding. Wonderful writing, on both levels.

-D.S. Atkinson

Five Stars

August 2, 2016

The pain is searing, but necessary - she has honored them all.

-Anne Elezabeth Pluto

August 2, 2016

The pain is searing, but necessary - she has honored them all.

-Anne Elezabeth Pluto